This exhibition features information on manuscripts lost from the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, France and Belgium. To read more about a specific country's manuscripts, please press one of the buttons below.

United Kingdom The Netherlands France BelgiumThe United Kingdom

England's manuscripts were relatively safe during the Second World

War. When the war broke out, many libraries took extensive

precautions to move their manuscripts to safe areas (more information about that here). But unfortunately such precautions were not always available,

and some areas lost historical records during the war.

Plymouth: The Central Library of Plymouth

What happened?

Plymouth, located in the south west of the country and therefore far from the main battle lines, was considered relatively safe from aerial bombardment during the initial stages of the war. However, the situation changed rapidly when large portions of France fell under the occupation of German forces. Areas of England that had been considered safe suddenly became targets.1

In March and April 1941, a series of devastating aerial attacks destroyed huge swaths of the city center. In these attacks, the Central Library of Plymouth lost almost all of its holdings—approximately 100,000 volumes.2 Most of the items that were destroyed were modern. But this library had also held a small collection of historical charters and deeds of local interest. Some of these documents dated back to the medieval period. A complete inventory of what was lost is unfortunately unavailable because the material had not been catalogued in any detail prior to the war.3 The losses to medieval records that can be identified are limited.4

What was lost?

- A 1418 grant of land in East Stonehouse by the Lord of Eststonhous (East Stonehouse) Stephen Durnford (or Stephen Durneford; the Sheriff of Plymouth at the time)

- A 1433 record of indenture between one John Langman and the prior of Plympton, Nicholas Selman

- A collection containing six indentures related to the priory of Plympton

These records held importance for local history. Since the collections had not been catalogued or described prior to the war, they cannot be recreated beyond these brief descriptions.

Coventry: The Gulson Library

What happened?

Coventry, a key center of munitions production during the war, was

the target of devastating enemy aerial bombardment on November 14th

and 15th, 1940. In this attack, the city's Gulson Library was nearly

completely destroyed, along with its modern book collections. About

150,000 volumes were destroyed according to one wartime estimate.5

While most of the city's older records and manuscripts were held

elsewhere, some historical documents that had been placed in the

strong room of the Gulson library were destroyed.6

What was lost?

Several medieval guild records from Coventry have been lost in the

modern age. These losses are especially tragic because Coventry was

an important site for medieval theater and these lost records

contained valuable information about the city's medieval plays. It

is worth noting, though, that many of the guild records that are now

lost were not destroyed during the Second World War, but about 60

years earlier, in a fire at the Birmingham Central Library.7 During

the Second World War, three historical collections of guild records

were destroyed, all of which were copied after 1500. More

information about the destruction at Coventry is available here.

The Netherlands

After the invasion of The Netherlands, several Dutch libraries lost medieval manuscripts to occupiers, who forced these libraries to send archival material to Germany.8 Relatively few medieval manuscripts were lost due to enemy bombardment. However, the collection of the Provincial Library of Zeeland unfortunately suffered losses when Middelburg was attacked.

Middelburg: The Provincial Library of Zeeland (now the Zeeuwse Bibliotheek)

What happened?

Middelburg suffered significant damages when the city was bombed on

May 17th, 1940. In this attack, about 600 buildings were destroyed.9

Among the destroyed buildings was the Provinciale Bibliotheek of

Zeeland (or the Provincial Library of Zeeland), which had been

founded in 1859. The library's current conservator, Marinus Bierens,

writes that about 160,000 books were destroyed in the attack. Only

about 20,000 remained, with many of those remaining suffering damage

from fire and from the water used to extinguish it.10 Witnesses

reported seeing pages of paper and parchment drift down from the

sky.11

At the time of the attack, the library was home to a collection of 800 items - mostly print books but also some manuscripts - that had been collected by the Ministerie van Predikanten back in the sixteenth century.12 The library was also home to the manuscript collection of the Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen (Zeeland Research Society). This research society, which was founded in 1769, held a rich collection of manuscripts at the time, owing, in part, to a rule that every member had to donate a valued object or manuscript to the society.13 When the library was destroyed, many of the Society's precious historical manuscripts were destroyed along with it. Aside from these collections, the Provincial Library had held another historical collection at the time: the library that had been in the vestry ('consistorie') of the Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church) in Vlissingen, which had been moved to the Provincial Library for its protection in 1939. The current conservator of the collection writes that when this collection from Vlissingen was catalogued in 1882, it contained 591 titles (most of which were early modern). He adds that all that remains of this collection today is 381 items, some of which are multivolume works. Many of these remaining items are damaged.14

What was lost?

Most of the manuscripts that were destroyed in the attack were from the eighteenth or nineteenth century, since this later period was particularly well represented in the library's manuscript collection.15 However, the library also lost some manuscripts that were older (from the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries). Among the older collections of the Zeeland Research Society were many manuscripts, charters, and other documents from the region, and many of the manuscripts that were lost were important for local history. These include a charter with a seal concerning the transfer of a local chapel. For a list of manuscripts that were destroyed, see the project catalogue.

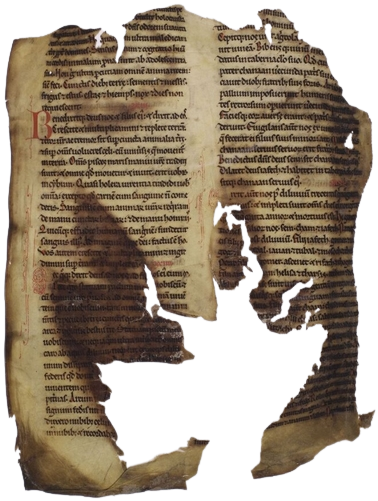

Some manuscripts survived but are badly damaged; one of these, a fifteenth-century biblical manuscript, is pictured here.

Example: A Manuscript from Zeeland

One of the manuscripts that was lost from Zeeland contained a

medieval copy of a work by the well-known ancient Greek philosopher

Aristotle. Here are the details about that manuscript:

Reference: Inventaris no. viii B16

Headnote:

Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics

Date: 15th century (1445)

Folia: unknown

Material: parchment

Provenance:

donated to the Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen by Aj de

Ruever from Zierikzee.

Contents:

Text: A Latin

translation of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics (translation

completed around 1443)

France

Chartres: The Municipal Library of Chartres

What happened?

During the tragic air battle on May 26th, 1944, Chartres was hit by

American bombs, and the municipal library was almost entirely

destroyed. On June 9th, 1944, the manuscripts that could be salvaged

were sent to the Bibliothèque nationale de France for restoration

work.17 Decades of careful work have been dedicated to repairing the

damaged manuscripts and to analysing and identifying the surviving

fragments.

What was lost?

The Municipal Library of Chartres manuscript collection was of great value, containing a remarkable number of Carolingian manuscripts (more information about the significance of the collection is available here.

According to Dominique Poire of the IRHT, "of the 518 listed manuscripts, 45% were totally destroyed" (this means about 233 were destroyed).18 About 248 manuscripts survive, some of which have been heavily damaged.19 A list of destroyed manuscripts and their contents is available here.

Example: A Manuscript Lost from Chartres

One of the manuscripts that was lost from Chartres contained

Guillelmus Peraldus' Summa de vitiis. This work was a widely

popular manual for priests about how to conduct confession by asking

the penitent about various sins. It treats gluttony, lust, greed,

sloth, pride, envy, wrath and the "sins of the tongue" (often in

that order). Many other copies of the

Summa de vitiis survive. This copy is fascinating because it

was produced within decades of when Peraldus' Summa de vitiis was

written. Here are the details about this manuscript:

Shelfmark

: Bibliothèque municipale de Chartres, MS 204 (228)20

Headnote :

Guillelmus Peraldus, Summa de vitiis

Date: 13th century

Folia: 193

Material: Parchment

Size : 300 x 200 mm

Decoration: Red ink ornaments

Provenance: Chapter of

Notre-Dame Cathedral, Chartres

Contents:

ff. 1-7: Table

of contents (in a more recent hand)

Incipit: "Incipit moralis

tractatus in VIItem viciis. Dicturi de singulis viciis..

ff.

7v-198: Guillelmus Peraldus, Summa de vitiis

Incipit:

"Pro XI francis, tractatus de VII visciis et remediis eorumdem usque

ac (sic) XXti quatuor libros.

Explicit:

"Explicit summa de viciis. / Explicit hic liber, sit scriptor

crimine liber. /Explicit, expliceat, ludere scriptor eat."

Note: More on Peraldus' Summa de vitiis is

available here.

The explicit of the text in this manuscript resembles one in the Lawrence J. Schoenberg Collection MS no. ljs216.

Tours: The Tours Municipal Library

What happened?

On June 19th, 1940, the Tours Municipal Library, and almost all of its collections, were tragically destroyed when approaching German forces threw incendiary shells into the library building. In the lead up to the destruction, the conservator of the collection, Georges Collon, had known that battle along the Loire line was imminent and had wanted to move the library's books and manuscripts to protect them. Unfortunately fuel and transport shortages made such a move impossible. Ultimately, the library staff had moved the books and manuscripts into a makeshift shelter and into the cellar of the library.21

What was lost?

A significant portion of the medieval manuscripts from the Tours Municipal library's collection originated from the older religious houses of the region, including Saint-Gatien de Tours, Saint-Martin de Tours, and l'Abbaye de Marmoutier. Many of the collection's older manuscripts, which had been placed in the basement of the library for safe keeping, survived the war. According to Collon, when they checked in early October that year, 816 manuscripts that had been placed in the basement were found. Still, many manuscripts were tragically destroyed. Collon estimated that about 1200 manuscripts in total had been lost.22 Only a portion of these were medieval. Prior to the war, the collection had held about 742 manuscripts that had been copied before 1500; of these, over 250 were destroyed. Information about the medieval manuscripts that were destroyed, including references to them from prior to the war, is available in the project catalogue.

Example: A Manuscript from Tours

One of the manuscripts that was lost from Tours contained Jean

Gerson's Homily on the Passion in French. This tract is based

on a sermon preached in 1402 by the theologian and writer Jean

Gerson (1363-1429). The Tours manuscript was notable for being among

the earliest copies of Gerson's text. Here are some details about

this manuscript:

Shelfmark: Tours Municipal Library MS 53223

Headnote: Jean Gerson's Homily on the Passion in French

Date: first quarter of the 15th century

Folia: 163

(followed by 6 blank folia)

Material: Parchment

Size:

150 x 100 mm

Contents:

ff. 1-163: Jean Gerson's Homily

on the Passion

Incipit: "[Ad] Deum vadit"

Explicit (f.

163): "... La poursuite de cecy est touchée, partie en la Passion

dessus dicte, partie ou livre qui se no ..."

Note: Other

copies of this text include Bibliothèque nationale de france, Fonds

fr. 24841.24

Metz: The Municipal Library of Metz

What happened?

During the early stages of the war, the Municipal Library in Metz placed their manuscript and incunabula collection in large bundles and cases and moved these out of the library to protect them from wartime damage. The collection was ultimately placed for safe-keeping in Fort Manstein (also known as Fort Girardin) on Mount St. Quentin.25

During the war, this fort was used as a munitions reserve by the occupying forces. On Sept. 1st 1944, while the Allied troops were advancing toward Metz, the occupying forces received an order to destroy their munitions reserves to prevent the Allied forces from using them. The reserves of Fort Manstein were set ablaze, and with them the collections of the municipal library of Metz.

What was lost?

The fire at Metz was disastrous. Of the 1475 manuscripts stored in the fort, 726 (almost half) were lost during the war, according to one estimate.26 This loss is tragic, especially since the manuscript collection of Metz was of considerable historical value. Most of the manuscripts in the collection's ancien fonds (MSS no. 1-750) were gathered during the French Revolution, when they had been taken from the religious houses of the region, including the local cathedral, the collégiale de Saint-Sauveur, and the abbeys of Saint-Arnould, Saint-Vincent, Saint-Clément, Saint-Symphorien and many more.27 These ancient fonds trace the social, political, and cultural history of medieval Metz. The manuscripts in the nouveau fonds (MSS 750 to 1475) are mostly on the history of Metz; they include a large collection from the former town hall and several other acquisitions and donations - including the collection of the Baron de Salis (d. 1892) - that reflect the history of the Lorraine region.28 For a list of manuscripts that were destroyed and information about them from prior to the war, see the project catalogue.

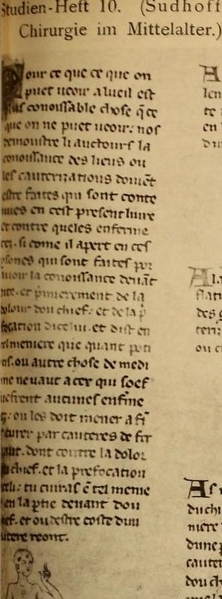

Example: A Manuscript from Metz

One of the manuscripts lost from Metz contained a French translation

of an influential Arabic surgical text. A specialist working on the

history of medicine had taken photos of this manuscript before the

war, but unfortunately his original photos were also destroyed

during the war.29 Thankfully, however, some of these photos had been

printed in a study of the medieval history of surgery by Karl

Sudhoff (1914); one of these has been included here.

Here are the details about this manuscript:

Shelfmark: Metz,

Bibliothèque municipale MS 122830

Headnote: Surgical text

Date: 15th century

Folia: 185, in 2 columns

Size:

230 x 100 mm

Decoration: Many illuminations, 19 of which had

been cut out

Provenance: the MS was acquired by the municipal

library from the collection of the Baron de Salis, who died in 1892.

The Baron had likely acquired it in 1849, when he bought a

collection of manuscripts from Théodore Tarbé, a printer and

bookseller in Sens. Many of Tarbé's manuscripts had come from the

library of Vauluisant (a Cistercian house); this manuscript may be

one of them.31

Contents:

ff. 1-97: Surgical text ascribed

to Bruno de Longoburgo, beg. "C'est la cyrurgie maistre Bruno de

Loncborc, et est intitulée"; (fol. 94v) "En l'an de l'Incarnation

Nostre Seignor ...je Bruno de Loncborc ai mis fin à ceste présente

œuvre..."

ff. 97-end: Chirurgie d'Albucasis

Incipit :

"Ce sont li chapitre d'Albugasys dou premier livre."

Note:

Short fragments of this text were printed before the war by Karl

Sudhoff (1914). There is a similar copy in Bibliothèque nationale de

France, fonds fr. 1318.32

Belgium

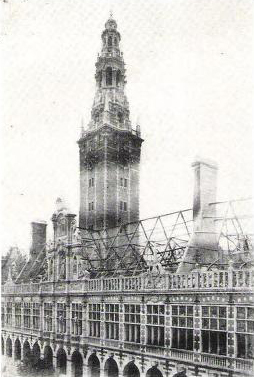

Leuven: The Library of the Catholic University of Leuven

What happened?

Leuven had suffered a tragic library fire during First World War. In late August 1914, German troops had set fire to the fifteenth-century library of Leuven (or Louvain), destroying countless medieval manuscripts.33 After the war, Germany and other nations had transferred a large number of medieval manuscripts to Belgium to help rebuild their damaged collections. But during the early stages of the Second World War, tragedy struck again. In May 1940, the Library of the Catholic University of Leuven was burnt down a second time.

What was lost?

In this tragedy, over 800 manuscripts (medieval and modern) were

lost.34 More information about these losses, and an example of these

losses, is

available here.

Tournai: The Tournai Municipal Library

What happened?

On May 17th 1940, the Bibliothèque de la ville de Tournai (Tournai Municipal Library) was destroyed in a German air raid. The library lost a vast collection, including about 70,000 books, and almost all of the collection's 247 manuscripts. Only 25 manuscripts of the pre-war collection were saved; this was thanks to the efforts of M. Coinne, the caretaker of the collection.35 Of the destroyed manuscripts, 42 (one of which is in two volumes) were produced before 1500.36

At the time of its destruction, the collection was in the process of being catalogued by Paul Faider and it is thanks to Faider's work that we still possess detailed information about many of the destroyed manuscripts. Unfortunately, however, Faider's work was brought to a halt in 1940, first by the tragic destruction of the collection in May and then by his untimely death in October of the same year. Faider's catalogue therefore covers only 120 of the collection's manuscripts.

Aside from the collection of the Tournai Municipal Library, the collection of the bishopric, housed nearby, was also destroyed in the same air raid. This collection, which contained about 60 manuscripts (both medieval and modern) at the time of its destruction had unfortunately not been catalogued before it was destroyed and cannot be recreated. Among the bishopric's valuable holdings was an eleventh-century manuscript containing excerpts of Ovid's Metamorphoses, along with other texts.37

What was lost?

Many of the manuscripts of the Tournai Municipal Library had come from the library of the local Cathedral Chapter. Throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the library had been enriched by the donations of local layfolk. As Tournai evolved into a rich centre of intellectual culture in the ensuing centuries, the library's collections benefitted from further donations.38 Among these were the books of the canon and bibliophile Denis (or Denys) de Villers, including Latin classics such as the works of Ovid and Prosper, and vernacular "bestsellers" - including the Roman de la rose, and the works of Froissart and Geoffrey of Monmouth (some of these works survived).39 Some of the manuscripts of the Cathedral Chapter were selected for the collection of the central library in Mons, while others were kept in Tournai and eventually became part of the Tournai Municipal Library's collection when the library opened to the public in 1818.40 The collection was therefore of significant historical importance and the loss of these important manuscripts has far reaching consequences. For a list of medieval manuscripts that were destroyed, see the project catalogue.

Example: A Manuscript Lost from Tournai

One of the manuscripts lost from Tournai contained a copy of Bede's

Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (or,

Ecclesiastical History of the English People). This was a

widely popular text, not just in England but also across the

channel. This manuscript also contained Cædmon's Hymn, which

is among the earliest known poems in the English language.

Shelfmark: Tournai Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 13441

Headnote:

Beda De Gestis Anglorum

Date: 12th century

Folia: 123

Material: Parchment

Size: 280 x 190 mm (writing area

205x 125 mm); 2 columns

Binding: 18th century leather binding

with the title "Beda De Gestis Anglorum"

Provenance: From

England; origin unknown (probably the same library as MS 135, the

thirteenth-century copy of Geoffrey of Monmouth that follows in the

catalogue). Later owned by Denis de Villers (d. 1620), canon of

Tournai; from him it passed to the Cathedral Chapter and then to the

municipal library.

Contents:42

ff. 1r-108v: Bede's

Historia ecclesiastica (in Latin)

Incipit: "Gloriossissimo

regi ceolwlfo Beda famulus Christi et presbiter"

Explicit:

"diligenter annotare curaui; apud omnes fructum pie intercessionis

inueniam. [and in a later hand, of the fifteenth or sixteenth

century:] Explicit liber de gestis anglorum amen"

Includes:

f. 78v: Cædmon's Hymn: West Saxon

Version (in the bottom margin; possibly the same hand)

Incipit: "Nu we sceolan herian heofonrices weard"

Explicit: "a middan eard mancynnes weard ece drihten æfter

teode | firum foldan. frea ælmihtig"

Facsimile and transcription

Another facsimile43

ff. 108v-123r: Rogerus [Fordani monasterii monachus], Carmina

et epistolae

Incipit: "Dilecto suo Galieno Rog[erus] [the

preceding in red ink] Carmina scribo tibi ueteri nouus hostis amico"

ff. 123v: Bulla Alexandri tertii papae de Thomae Becket

occisione

Incipit: "Alexander seruus seruorum dei venerabili

fratri Barthol[omeo]

Note: This lost manuscript, which

contained a copy of Bede's Historia ecclesiastica, was notable

because the English text of Cædmon's Hymn is written in the margin

of Bede's Latin text (in other versions this English text

interpolated into Bede's text).

Footnotes

- C. E. Welch, "Local Archives of Great Britain: The Plymouth Archives Department." Archives 5, no. 26 (1961): pp. 100-105.

- See Arthur der Weduwen and Andrew Pettegree, The Library: A Fragile History (London: Profile Books, 2021).

- "Local Archives", Archives 5, no. 26 (1961): pp. 100-105.

- C. W. Bracken, "[no title]", Devon and Cornwall Notes and Queries, 22 (1942-1946), pp. 138, 151, 181.

- Libraries and Museum Committee. The Coventry Libraries: Report of the Committee on the Work of the Libraries for the Period 1st April 1940 to 31 March 1942 (Coventry: Libraries and Museum Committee, 1942).

- On this topic, see Krista A. Milne, "Early English Drama Records and Other Manuscripts from Coventry Destroyed Before and During the Second World War." Early Theatre 26, no. 2 (2023), pp. 33-55.

- For those who attribute these losses to the war, see e.g. Reginald W. Ingram, Records of Early English Drama: Coventry (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981), pp. li; lxvi-lxvii. On the fire at the Birmingham Reference Library, see Pamela King and Clifford Davidson's "Introduction," in The Coventry Corpus Christi Plays, ed. by Pamela King and Clifford Davidson (Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 2000), 2-81, p. 2.

- See the examples given by T. P. Sevensma in "Een geslaagde ruil van handschriften," De Gids, 110 (1947), pp. 26-35.

- "De verwoesting van Middelburg op 17 mei 1940", Zeeuws Archief, n.d., https://www.zeeuwsarchief.nl/zeeuwse-verhalen/tweede-wereldoorlog/de-verwoesting-van-middelburg-op-17-mei-1940/.

- Bierans, "Zeeland," p 144; "Handschriften," Koninklijk Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen, n.d. https://kzgw.nl/collecties/handschriften/.

- "Handschriften"

- Bierans, "Zeeland," p. 148.

- "Handschriften"

- Bierans, "Zeeland," p. 150.

- "Handschriften." The manuscripts are described in J.P. van Visvliet, Inventaris der handschriften van het Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen, (Middelburg: J.C. & W. Altorffer, 1861), and F. Nagtglas, Vervolg op den Inventaris der handschriften van het Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen (Middelburg: J.C. & W. Altorffer, 1869).

- Described in Van Visvliet, Inventaris, p. 74.

- "L'incendie et ses conséquences," À la recherche des manuscrits de Chartres, 2022, https://www.manuscrits-de-chartres.fr/fr/incendie-et-ses-cons%C3%A9quences.

- Laure Cailloce, "Bringing the Chartres Manuscripts Back to Life," CNRS News, March 26th, 2018. https://news.cnrs.fr/articles/bringing-the-chartres-manuscripts-back-to-life.

- "À la recherche des manuscrits de Chartres," À la recherche des manuscrits de Chartres, 2022,https://www.manuscrits-de-chartres.fr/fr

- "Bibliographie," À la recherche des manuscrits de Chartres, 2022. https://www.manuscrits-de-chartres.fr//fr/bibliographie#biblio, p. 182; https://www.manuscrits-de-chartres.fr/fr/manuscrits/chartres-bm-ms-204 and https://ccfr.bnf.fr/portailccfr/jsp/index_view_direct_anonymous.jsp?record=eadcgm:EADC:D17011196 ; Ministère de l'éducation nationale, Le Catalogue général des manuscrits: Tome 11, Chartres (Paris: Librarie Plon), p. 104.

- Daniel Schweitz, "L'incendie de la bibliothèque de Tours (juin 1940)," Histoire de la Touraine, edited by Pierre Leveel (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1956), pp. 183-202, p. 186.

- Schweitz, "L'incendie," pp. 193; 197.

- "532. Jean Gerson. Homélie sur la Passion, en français," Catalogue collectif de France, n.d. https://ccfr.bnf.fr/portailccfr/ark:/06871/004D37A15878

- See the edition in The Ad Deum vadit of Jean Gerson, edited by D. H. Carnahan (Illinois: U of Illinois Studies in Language and Literature, 1917).

- "Les manuscrits disparus de la Bibliothèque de Metz," Le Républicain Lorrain, 2017, https://www.republicain-lorrain.fr/actualite/2017/02/14/les-manuscrits-disparus-de-la-bibliotheque-de-metz.

- "Les manuscrits disparus." More information is available in Krista A. Murchison, "Righting and Rewriting History: Recovering and Analysing Manuscript Archives Destroyed During World War II," Queeste, 1 (2019): pp. 98-102.

- Ministère de l'éducation nationale, Le Catalogue général des manuscrits des bibliothèques publiques des départements: Tome 5, Metz. Verdun. Charleville (Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1879), p. 5.

- Ministère de l'éducation nationale, Le Catalogue: Tome 5, pp. xiii-xxxxiv.

- See Trotter, Traitier, pp. 4-5.

- See Ministère de l'éducation nationale, Le Catalogue général des manuscrits: Tome 48, mss 1030-1475 (Paris: Librarie Plon, 1933), https://archive.org/details/cataloguegnr48fran/; Léopold Delisle, "Les manuscrits du baron de Salis," Bibliothèque De L'École Des Chartes 55 (1894): pp. 560-62 (where it is listed as item 78); David Trotter, Traitier De Cyrurgie (Boston: De Gruyter, 2005); and Murchison, "Righting."

- Petitmengin Bougard, et al. La Bibliothèque De L'abbaye Cistercienne De Vauluisant: Histoire Et Inventaires. (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2012).

- See Karl Sudhoff, Beitraäge Zur Geschichte Der Chirurgie Im Mittelalter: Graphische Und Textliche Untersuchungen in Mittelalterlichen Handschriften (Leipzig: Barth, 1914), and Murchison, "Righting."

- Printed in the Library Association, "The Destruction of Louvain's Library," Library Journal 39, no. 10 (1914), p. 763, quoted at p. 763.

- Hans Van der Hoeven, Lost Memory: Libraries and Archives Destroyed in the Twentieth Century (Paris: UNESCO, 1996), p. 13.

- Paul Faider, and Pierre Van Sint-Jan, eds, Catalogue des manuscrits conservés à Tournai: Bibliothèques de la ville et du séminaire, vol. 6 (Gembloux: J. Duculot, 1950), p. 3. Other manuscripts were added to the collections after the library was damaged; see the table on p. 17.

- The count of 247 is given in Faider, and Van Sint-Jan, Catalogue, p. 3. The count is based on the manuscripts described in Amable Wilbaux, Catalogue de la bibliothèque de la ville de Tournai, vol. 1 (Tournai: Typ. de H. Casterman, 1869). Wilbaux enumerates manuscripts up to no. 245, but one of these manuscripts, no. 3, is in three parts. The count of lost medieval manuscripts is mine.

- Faider and van Sint Jan, eds. Catalogue, p. 3.

- Faider and van Sint Jan, eds. Catalogue, pp. 2-5.

- Faider and van Sint Jan, eds. Catalogue, pp. 5-6.

- Faider and van Sint Jan, eds. Catalogue, pp. 9-10; 14.

- Faider and van Sint Jan, eds. Catalogue, pp. 149-153.

- "Tournai, Bibliothèque Municipale, 134," The Production and Use of English Manuscripts 1060 to 1220, edited by Orietta Da Rold et al., 2013, https://www.le.ac.uk/english/em1060to1220/mss/EM.To.BM.134.htm.

- A facsimile is printed in Fred C. Robinson, and E.G. Stanley's Old English Verse Texts from Many Sources: A Comprehensive Collection (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1991), 2.20.